Git is super useful for anyone doing a bit of development work or just trying to keep track of a bunch of text files. However, as your project grows you might find yourself doing lots of boring repetitive work just around Git itself. At least that’s what happened to me and so I automated some boring Git stuff using our continuous integration (CI) system.

There are probably all sorts of use cases for automating various Git operations but I’ll talk about a few that I’ve encountered. We’re using GitLab and GitLab CI so that’s what my examples will include, but most of the concepts should apply to other systems as well.

Automatic rebase

We have some Git repos with source code that we receive from vendors, who we can think

of as our upstream. We don’t actually share a Git repo with the vendor but

rather we get a tar ball every now and then. The tar ball is extracted into a

Git repository, on the master branch which thus tracks the software as it is

received from upstream. In a perfect world the software we receive would be

feature complete and bug free and so we would be done, but that’s usually not

the case. We do find bugs and if they are blocking we might decide to implement

a patch to fix them ourselves. The same is true for new features where we might

not want to wait for the vendor to implement it.

The result is that we have some local patches to apply. We commit such patches

to a separate branch, commonly named ts (for TeraStream), to keep them

separate from the official software. Whenever a new software version is released,

we extract its content to master and then rebase our ts branch onto master

so we get all the new official features together with our patches. Once we’ve

implemented something we usually send it upstream to the vendor for inclusion.

Sometimes they include our patches verbatim so that the next version of the code

will include our exact patch, in which case a rebase will simply skip our patch.

Other times there are slight or major (it might be a completely different design)

changes to the patch and then someone typically needs to sort out the patches

manually. Mostly though, rebasing works just fine and we don’t end up with conflicts.

Now, this whole rebasing process gets a tad boring and repetitive after a while, especially considering we have a dozen of repositories with the setup described above. What I recently did was to automate this using our CI system.

The workflow thus looks like:

- human extracts zip file, git add + git commit on master + git push

- CI runs for

masterbranch- clones a copy of itself into a new working directory

- checks out

tsbranch (the one with our patches) in working directory - rebases

tsontomaster - push

tsback toorigin

- this event will now trigger a CI build for the

tsbranch - when CI runs for the

tsbranch, it will compile, test and save the binary output as “build artifacts”, which can be included in other repositories - GitLab CI, which is what we use, has a CI_PIPELINE_ID that we use to version built container images or artifacts

To do this, all you need is a few lines in a .gitlab-ci.yml file, essentially;

stages:

- build

- git-robot

... build jobs ...

git-rebase-ts:

stage: git-robot

only:

- master

allow_failure: true

before_script:

- 'which ssh-agent || ( apt-get update -y && apt-get install openssh-client -y )'

- eval $(ssh-agent -s)

- ssh-add <(echo "$GIT_SSH_PRIV_KEY")

- git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

- git config --global user.name "Mr. Robot"

- mkdir -p ~/.ssh

- cat gitlab-known-hosts >> ~/.ssh/known_hosts

script:

- git clone [email protected]:${CI_PROJECT_PATH}.git

- cd ${CI_PROJECT_NAME}

- git checkout ts

- git rebase master

- git push --force origin ts

We’ll go through the Yaml file a few lines at a time. Some basic knowledge about GitLab CI is assumed.

This first part lists the stages of our pipeline.

stages:

- build

- git-robot

We have two stages, first the build stage, which does whatever you want it to

do (ours compiles stuff, runs a few unit tests and packages it all up), then the

git-robot stage which is where we perform the rebase.

Then there’s:

git-rebase-ts:

stage: git-robot

only:

- master

allow_failure: true

We define the stage in which we run followed by the only statement which limits

CI jobs to run only on the specified branch(es), in this case master.

allow_failure simply allows the CI job to fail but still passing the pipeline.

Since we are going to clone a copy of ourselves (the repository checked out in CI) we need SSH and SSH keys set up. We’ll use ssh-agent with a password-less key to authenticate. Generate a key using ssh-keygen, for example:

ssh-keygen

kll@machine ~ $ ssh-keygen -f foo

Generating public/private rsa key pair.

Enter passphrase (empty for no passphrase):

Enter same passphrase again:

Your identification has been saved in foo.

Your public key has been saved in foo.pub.

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:6s15MZJ1/kUsDU/PF2WwRGA963m6ZSwHvEJJdsRzmaA kll@machine

The key's randomart image is:

+---[RSA 2048]----+

| o**.*|

| ..o**o|

| Eo o%o|

| .o.+o O|

| So oo.o+.|

| .o o.. o+o|

| . . o..o+=|

| . o .. .o= |

| . +. .. |

+----[SHA256]-----+

kll@machine ~ $

Add the public key as a deploy key under Project Settings Repository Deploy Keys. Make sure you enable write access or you won’t be able to have your Git robot push commits. We then need to hand over the private key so that it can be accessed from within the CI job. We’ll use a secret environment variable for that, which you can define under Project Settings Pipelines Environment variables). I’ll use the environment variable GIT_SSH_PRIV_KEY for this.

Next part is the before_script:

before_script:

- 'which ssh-agent || ( apt-get update -y && apt-get install openssh-client -y )'

- eval $(ssh-agent -s)

- ssh-add <(echo "$GIT_SSH_PRIV_KEY")

- git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

- git config --global user.name "Mr. Robot"

- mkdir -p ~/.ssh

- cat gitlab-known-hosts >> ~/.ssh/known_hosts

First ssh-agent is installed if it isn’t already. We then start up ssh-agent and add the key stored in the environment variable GIT_SSH_PRIV_KEY (which we set up previously). The Git user information is set and we finally create .ssh and add the known host information about our GitLab server to our known_hosts file. You can generate the gitlab-known-hosts file using the following command:

ssh-keyscan my-gitlab-machine >> gitlab-known-hosts

As the name implies, the before_script is run before the main script part and

the ssh-agent we started in the before_script will also continue to run for the

duration of the job. The ssh-agent information is stored in some environment

variables which are carried across from the before_script into the main script,

enabling it to work. It’s also possible to put this SSH setup in the main script,

I just thought it looked cleaner splitting it up between before_script and script.

Note however that it appears that after_script behaves differently so while it’s

possible to pass environment vars from before_script to script, they do not

appear to be passed to after_script. Thus, if you want to do Git magic in the

after_script you also need to perform the SSH setup in the after_script.

This brings us to the main script. In GitLab CI we already have a checked-out clone of our project but that was automatically checked out by the CI system through the use of magic (it actually happens in a container previous to the one we are operating in, that has some special credentials) so we can’t really use it, besides, checking out other branches and stuff would be really weird as it disrupts the code we are using to do this, since that’s available in the Git repository that’s checked out. It’s all rather meta.

Anyway, we’ll be checking out a new Git repository where we’ll do our work, then

change the current directory to the newly checked-out repository, after which

we’ll check out the ts branch, do the rebase and push it back to the origin remote.

- git clone [email protected]:${CI_PROJECT_PATH}.git

- cd ${CI_PROJECT_NAME}

- git checkout ts

- git rebase master

- git push --force origin ts

… and that’s it. We’ve now automated the rebasing of a branch in our config file. Occasionally it will fail due to problems rebasing (most commonly merge conflicts) but then you can just step in and do the above steps manually and be interactively prompted on how to handle conflicts.

Automatic merge requests

All the repositories I mentioned in the previous section are NEDs, a form of

driver for how to communicate with a certain type of device, for Cisco NSO (a

network orchestration system). We package up Cisco NSO, together with these NEDs

and our own service code, in a container image. The build of that image is

performed in CI and we use a repository called nso-ts to control that work.

The NEDs are compiled in CI from their own repository and the binaries are saved

as build artifacts. Those artifacts can then be pulled in the CI build of nso-ts.

The reference to which artifact to include is the name of the NED as well as the

build version. The version number of the NED is nothing more than the pipeline

id (which you’ll access in CI as ${CI_PIPELINE_ID}) and by including a specific

version of the NED, rather than just use “latest” we gain a much more consistent

and reproducible build.

Whenever a NED is updated a new build is run that produces new binary artifacts.

We probably want to use the new version but not before we test it out in CI. The

actual versions of NEDs to use is stored in a file in the nso-ts repository and

follows a simple format, like this:

ned-iosxr-yang=1234

ned-junos-yang=4567

...

Thus, updating the version to use is a simple job to just rewrite this text file

and replace the version number with a given CI_PIPELINE_ID version number. Again,

while NED updates are more seldom than updates to nso-ts, they do occur and

handling it is bloody boring. Enter automation!

git-open-mr:

image: gitlab.dev.terastrm.net:4567/terastream/cisco-nso/ci-cisco-nso:4.2.3

stage: git-robot

only:

- ts

tags:

- no-docker

allow_failure: true

before_script:

- 'which ssh-agent || ( apt-get update -y && apt-get install openssh-client -y )'

- eval $(ssh-agent -s)

- ssh-add <(echo "$GIT_SSH_PRIV_KEY")

- git config --global user.email "[email protected]"

- git config --global user.name "Mr. Robot"

- mkdir -p ~/.ssh

- cat gitlab-known-hosts >> ~/.ssh/known_hosts

script:

- git clone [email protected]:TeraStream/nso-ts.git

- cd nso-ts

- git checkout -b robot-update-${CI_PROJECT_NAME}-${CI_PIPELINE_ID}

- for LIST_FILE in $(ls ../ned-package-list.* | xargs -n1 basename); do NED_BUILD=$(cat ../${LIST_FILE}); sed -i packages/${LIST_FILE} -e "s/^${CI_PROJECT_NAME}.*/${CI_PROJECT_NAME}=${NED_BUILD}/"; done

- git diff

- git commit -a -m "Use ${CI_PROJECT_NAME} artifacts from pipeline ${CI_PIPELINE_ID}"

- git push origin robot-update-${CI_PROJECT_NAME}-${CI_PIPELINE_ID}

- HOST=${CI_PROJECT_URL} CI_COMMIT_REF_NAME=robot-update-${CI_PROJECT_NAME}-${CI_PIPELINE_ID} CI_PROJECT_NAME=TeraStream/nso-ts GITLAB_USER_ID=${GITLAB_USER_ID} PRIVATE_TOKEN=${PRIVATE_TOKEN} ../open-mr.sh

So this time around we check out a Git repository into a separate working

directory again, it’s just that it’s not the same Git repository as we are

running on simply because we are trying to do changes to a repository that is

using the output of the repository we are running on. It doesn’t make much of a

difference in terms of our process. At the end, once we’ve modified the files we

are interested in, we also open up a merge request on the target repository.

Here we can see the MR (which is merged already) to use a new version of the

NED ned-snabbaftr-yang.

What we end up with is that whenever there is a new version of a NED, a single merge

request is opened on our nso-ts repository to start using the new NED. That

merge request is using changes on a new branch and CI will obviously run for

nso-ts on this new branch, which will then test all of our code using the new

version of the NED. We get a form of version pinning, with the form of explicit

changes that it entails, yet it’s a rather convenient and non-cumbersome

environment to work with thanks to all the automation.

Getting fancy

While automatically opening an MR is sweet… we can do betterfancier. Our nso-ts

repository is based on Cisco NSO (Tail-F NCS), or actually the nso-ts Docker

image is based on a cisco-nso Docker image that we build in a separate

repository. We put the version of NSO as the tag of the cisco-nso Docker

image, so cisco-nso:4.2.3 means Cisco NSO 4.2.3. This is what the nso-ts

Dockerfile will use in its FROM line.

Upgrading to a new version of NCS is thus just a matter of rewriting the tag… but what version of NCS should we use? There’s 4.2.4, 4.3.3, 4.4.2 and 4.4.3 available and I’m sure there’s some other version that will pop up its evil head soon enough. How do I know which version to pick? And will our current code work with the new version?

To help myself in the choice of NCS version I implemented a script that gets the README file of a new NCS version and cross references the list of fixed issues with the issues that we currently have open in the Tail-F issue tracker. The output of this is included in the merge request description so when I look at the merge request I immediately know what bugs are fixed or new features are implemented by moving to a specific version. Having this automatically generated for us is… well, it’s just damn convenient. Together with actually testing our code with the new version of NCS gives us confidence that an upgrade will be smooth.

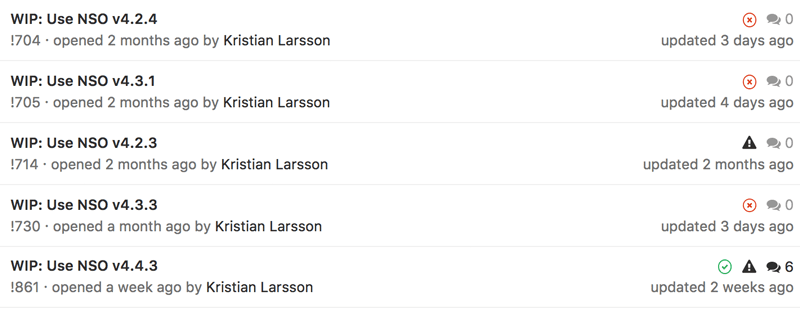

Here are the merge requests currently opened by our GitBot:

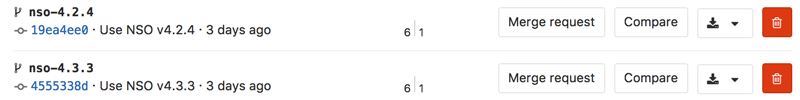

We can see how the system have generated MRs to move to all the different versions of NSO currently available. As we are currently on NSO v4.2.3 there’s no underlying branch for that one leading to an errored build. For the other versions though, there is a branch per version that executes the CI pipeline to make sure all our code runs with this version of NSO.

As there have been a few commits today, these branches are behind by six commits but will be rebased this night so we get an up-to-date picture if they work or not with our latest code.

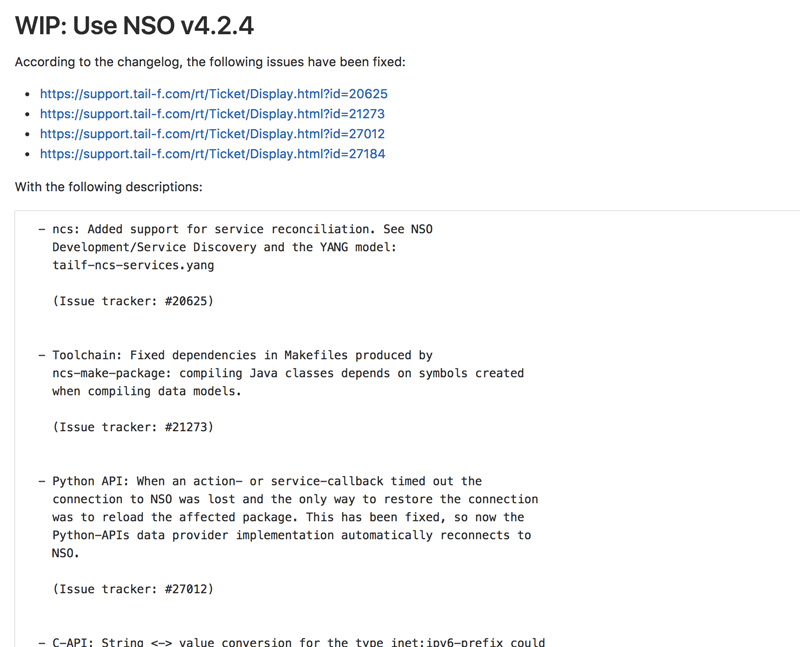

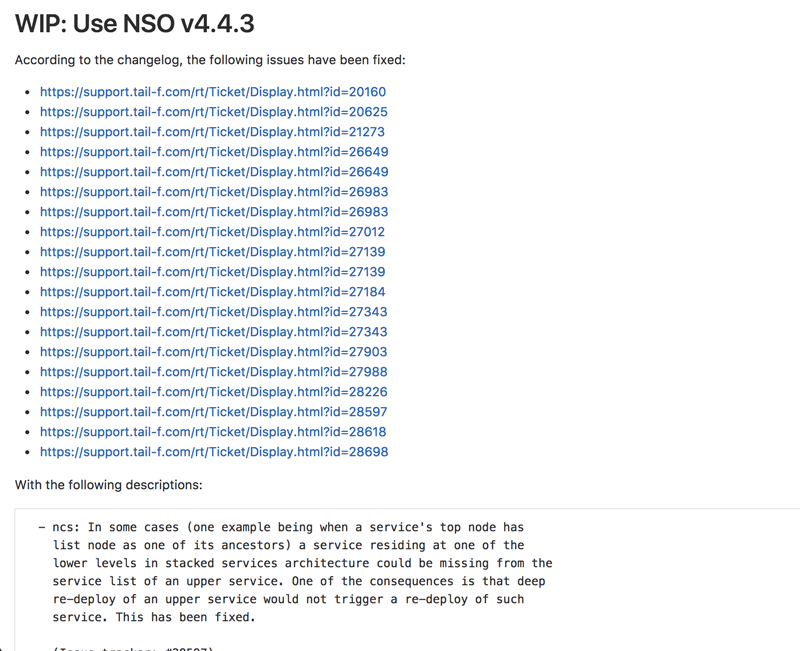

If we go back and look at one of these merge requests, we can see how the description includes information about what issues that we currently have open with Cisco / Tail-F would be solved by moving to this version.

This is from v4.2.4 and as we are currently on v4.2.3 we can see that there are only a few fixed issues.

If we instead look at v4.4.3 we can see that the list is significantly longer.

Pretty sweet, huh? :)

As this involves a bit more code I’ve put the relevant files in a GitHub gist.

This is the end

If you are reading this, chances are you already have your reasons for why you want to automate some Git operations. Hopefully I’ve provided some inspiration for how to do it.

If not or if you just want to discuss the topic in general or have more specific questions about our setup, please do reach out to me on Twitter.

This post was originally published on plajjan.github.io.

About the Guest Author

Kristian Larsson is a network automation systems architect at Deutsche Telekom. He is working on automating virtually all aspects of running TeraStream, the design for Deutsche Telekom's next generation fixed network, using robust and fault tolerant software. He is active in the IETF as well as being a representing member in OpenConfig. Previous to joining Deutsche Telekom, Kristian was the IP & opto network architect for Tele2's international backbone network.

"BB-8 in action by Joseph Chan on Unsplash